Why don’t we have more robots???

It's both the worst time and the best time to build them.

I have been spending more time reading science fiction, rather than sticking to my typical media diet of non-fiction. It's a genre full of vivid scenes of human life that is often augmented and aided by robots. Sometimes the robots themselves end up being the heroes or the villains. The imagination is not limited to humanoids, the perfect mechanical representation of humans, allowing us to dream of task-oriented robots that clean and cook, drive taxis and spaceships, and deliver goods. It does make me stop and wonder, why don’t we have more robots in our lives today?

Let's first lay some ground rules: when I say robots, I am referring to robo-taxis, autonomous vehicles, equipment with automated systems, humanoids, quadrupeds, and a small but growing set of industrial robotics1. Robots interact with physical space and autonomously make decisions to adapt their behavior in response to environmental factors and execute multi-step tasks. This differs from machines that can handle complicated actions, but do so without any intelligence. Just like washing machines and cars are machines, as long as they are in working order, they will do the same task the same way each time, regardless of the situation.

The robots we have today are nothing compared to the ideas science fiction writers have been able to come up with. Pixar imagined a world where all robots collect and compress the trash from Earth, dress hair, vacuum and mop floors, or even make toast. Daniel Suarez envisioned spacecraft and space-ready humanoid robots that are controlled via VR hand gestures, providing the user with tactile feedback. So far, all we have is a robot that vacuums.

Summary

What are the challenges restricting robot development and adoption?

All robots are custom-purpose.

We lack sufficient data for robotic general intelligence.

The physical labor of a human is difficult to automate.

Most robots have not been profitable.

Robots are worse at learning than humans.

How are things getting better?

The cost of many critical systems in the robot are getting cheaper.

The rise of the transformer model (AI).

Moore’s Law

What are the challenges restricting robot development and adoption?

Headwind #1: All robots are custom-purpose.

All robots to date that are adding real value are custom-purpose robots. It doesn’t matter if it is a robot straight from the manufacturer or a manual system that has autonomy technology added on top; these systems are built for a select reason. There are no general-purpose robots. The closest thing is likely FSD enabled Teslas.

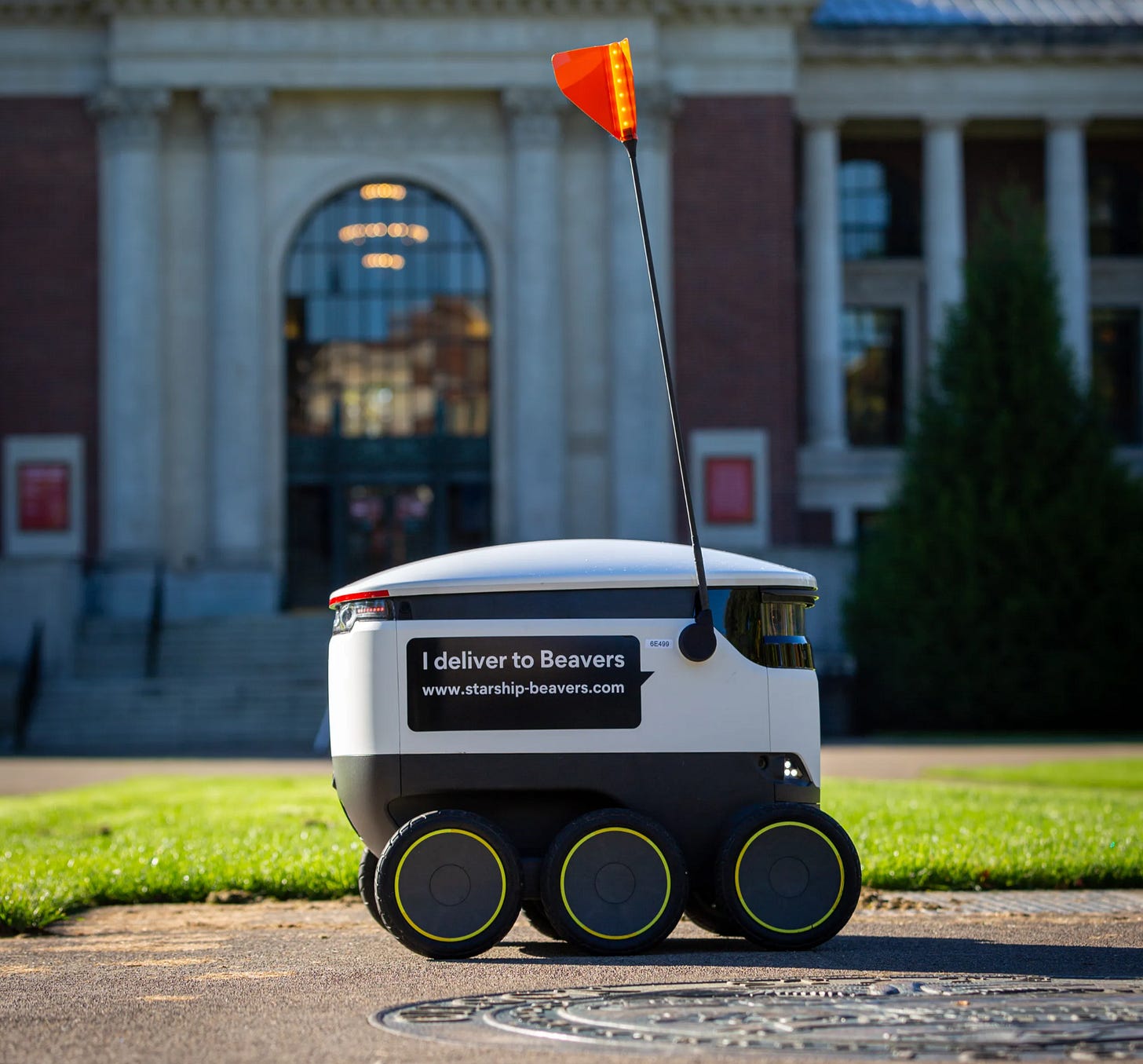

The specificity for which robots are built is often an advantage rather than a hindrance. It makes sense for a car to drive itself, rather than letting a humanoid robot sit in your driver’s seat, adjust your mirrors and seat position, and drive you around like a chauffeur. It makes more sense for a wheeled delivery rover to carry food from your local takeout spot to your house, rather than a humanoid make the same journey.

The robots that exist today are focused on where value can be created, which is 99.9% industry applications. Why? Well, robots are expensive to develop. Requiring years to design, build, test, and iterate on hardware until it can fill that application’s needs. Then teams need to scale up the supply chain, create tools for custom parts, and develop the production lines. Traditionally, the intelligence system was the slow part due to the level of research, data collection, training, and testing required. However, it has become a little easier for simpler robotic systems lately. Therefore, the use case for which each robot is developed must be able to bear the cost of this process.

As such, there is a relationship between the complexity of developing a robot, the price point at which the robot can be sold, and the volume of robots that are needed. The more complex the robot’s function is, the more time and money will be needed to create a viable solution, which requires more revenue to pay back that initial investment. To sustain this higher revenue, higher price point options can afford to have lower sales volumes, but lower price point options require higher numbers of sales to meet the same threshold. There are sweet spots, like the Roomba: low complexity, low price point, and moderate volume, and that of Pronto Ai2: moderate complexity, high price point, and low volume.

Most use cases today don’t fit this mold. I am no fan of laundry-folding robotics, which is 10 times more complex than a robotic vacuum cleaner with a smaller customer base. To achieve profitability, those systems would need to sell for the price of a used car, which most consumers will not accept. The situation is the same with robots that unload the dishwasher, mow the grass, or do other tedious 3-dimensional manipulation chores that we do around the house.

While custom-purpose robots are currently in the field, solving many problems better than a general-purpose robot likely would, they are only feasible under a select set of use cases, which limits the supply of robots.

Headwind #2: We lack sufficient data to train robotic general intelligence.

Robots need a different type of intelligence than their text-based chatbot cousins. The first generation of robots, designed to handle repetitive tasks and low environmental variability, relied on traditional machine vision applications to detect and locate objects, then maneuver around them. Many early on- and off-highway autonomous vehicles fall into this camp. They required tons of picture and video data, with objects clearly labeled, to train object detection models that identify specific types of objects and locate them in space. Over the past few decades, companies and researchers alike have generated massive datasets for training.

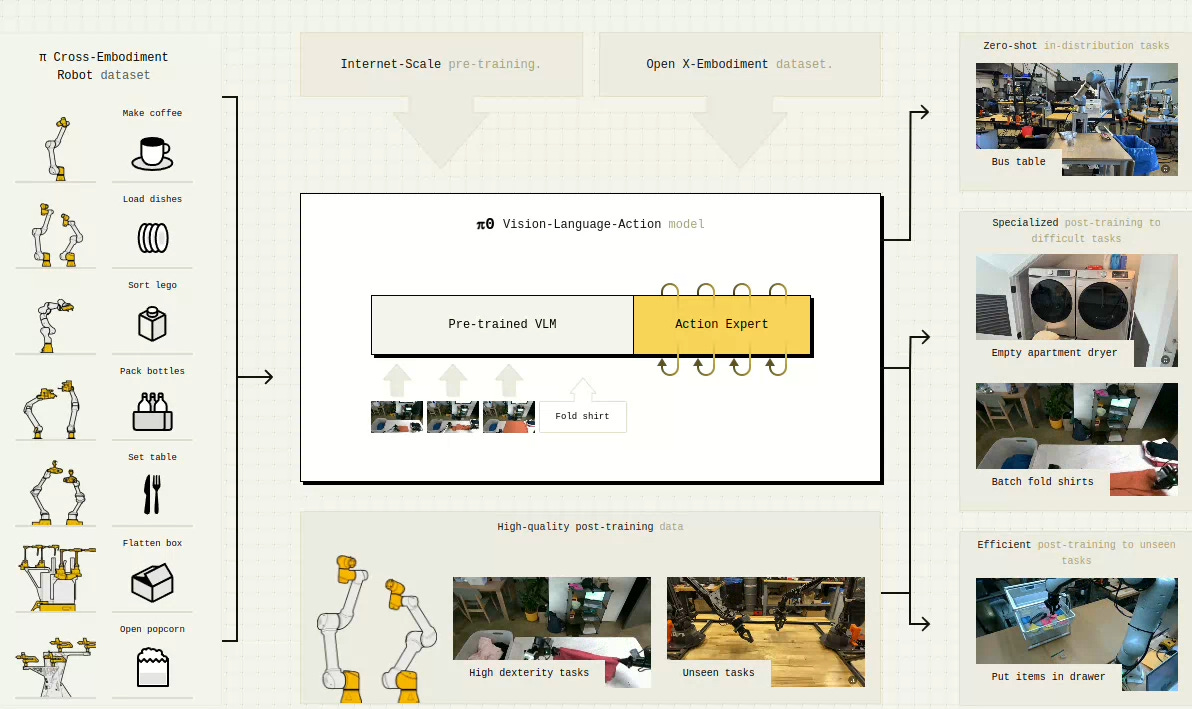

The next generation of robots is designed for more variable use cases, hence they require more flexible and complex intelligence. Enter the Vision-Language-Action models (VLAs). These new models incorporate visual observations, language commands, and the robot’s state, such as joint angles, force levels, and gripper states, to make decisions on the next action. Today, active research is ongoing to apply VLAs to all sorts of robots, including robotic arms, humanoids, drones, and autonomous vehicles. VLAs are comprised of multiple models, some are trained on the open internet, like the Vision-Language model (VLM)[3], others are trained during VLA pre-training. The VLA’s pre-training step is for adapting the general training of the VLM to that of the robot operating in the physical domain.

We need data to bridge the gap between a command and what actions the robot must take to accomplish it. The ideal case is high-quality datasets showing your specific robot completing your full set of actions. If you are a Frank Panda Arm, the DROID dataset has you covered. Most are not so lucky, so many people use robot analogs, such as similar model robots or humans standing in as robots, if the right conditions are met.

https://droid-dataset.github.io/

Much like a toddler learning to walk, a robot acquires new skills through a clumsy, trial-and-error process of incremental steps. However, we have far less tolerance for buggy robots than for learning children. We use data as the teacher, showing a robot how to avoid obstacles, grasp, pinch, or otherwise manipulate objects. This requires a concrete connection between the task and the robot's physical form, a challenge known as the embodiment problem. Because robot bodies are so diverse, from delivery drones to massive autonomous dump trucks, training data from one type will not transfer to another.

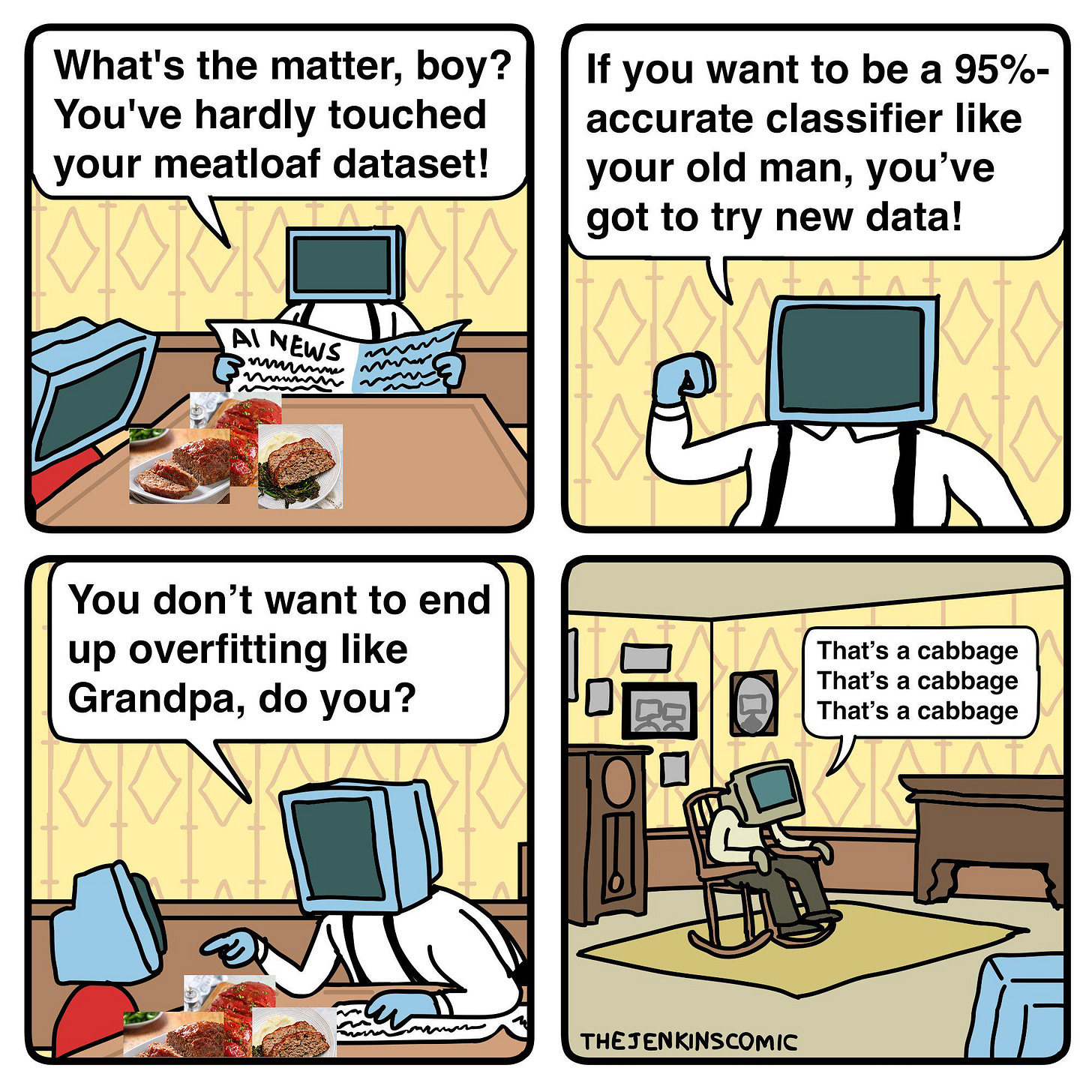

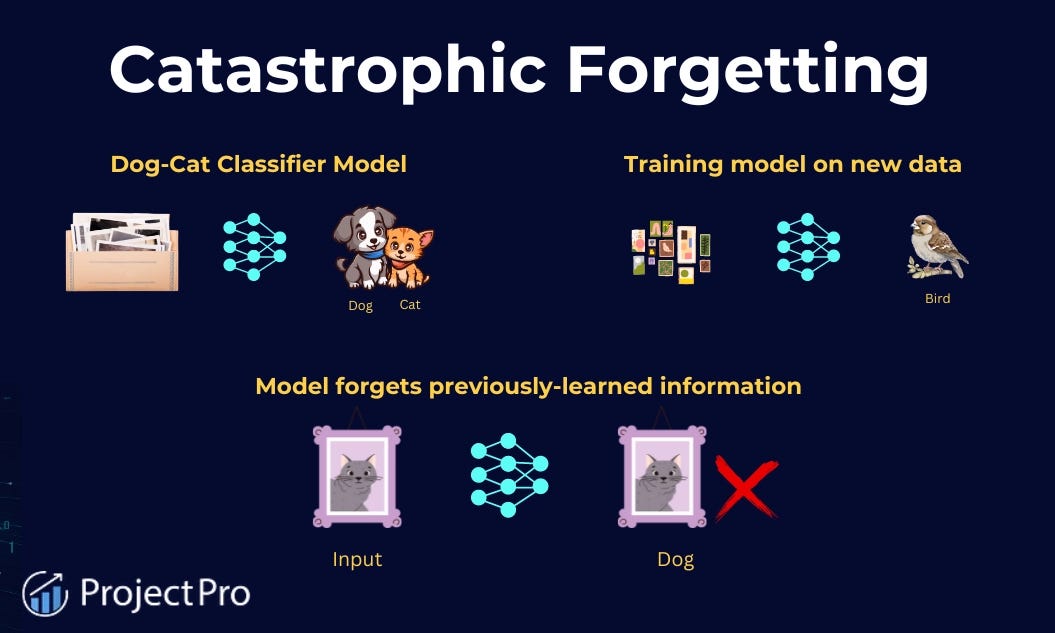

This problem is magnified by the sheer volume of data required for each unique robot body. While we have immense libraries of real and synthetic content to train VLMs on video, text, and images, we have very little of the physical interaction data needed for VLA models. Without vast and specific datasets for training, it becomes critically important to isolate a separate set of data for validation. This ensures the robot is truly learning a skill and not just "memorizing" the training examples, which could lead to catastrophic failure in the field.

Solving this data bottleneck will not happen overnight. It took us decades to build the general-purpose datasets of the internet that were used to train LLMs. To achieve a similar feat for robotics, we will need a diverse fleet of robots operating in the real world, continuously learning and collecting the physical interaction data required to train a truly generalized intelligence.

Headwind #3: Physical human labor is difficult to automate.

Humans have a diverse set of skills. We can communicate, walk around, avoid obstacles, pick things up, manipulate relatively heavy objects in 6 degrees of freedom, hold things of many different shapes and sizes, and do so collaboratively. Each of those steps would prove challenging for a robot. Many jobs require multiple skills to complete, necessitating the complexity of robots designed to fulfill them.

There are those jobs that require a few niche skills, that may be complicated, but are very routine, at which robots can compete. Robots, today, excel at routine tasks, especially complicated ones, that are conducted many times a day. This is where greater efficiency, reliability, and a lack of fatigue of a robot’s actions shine when compared to its human counterpart.

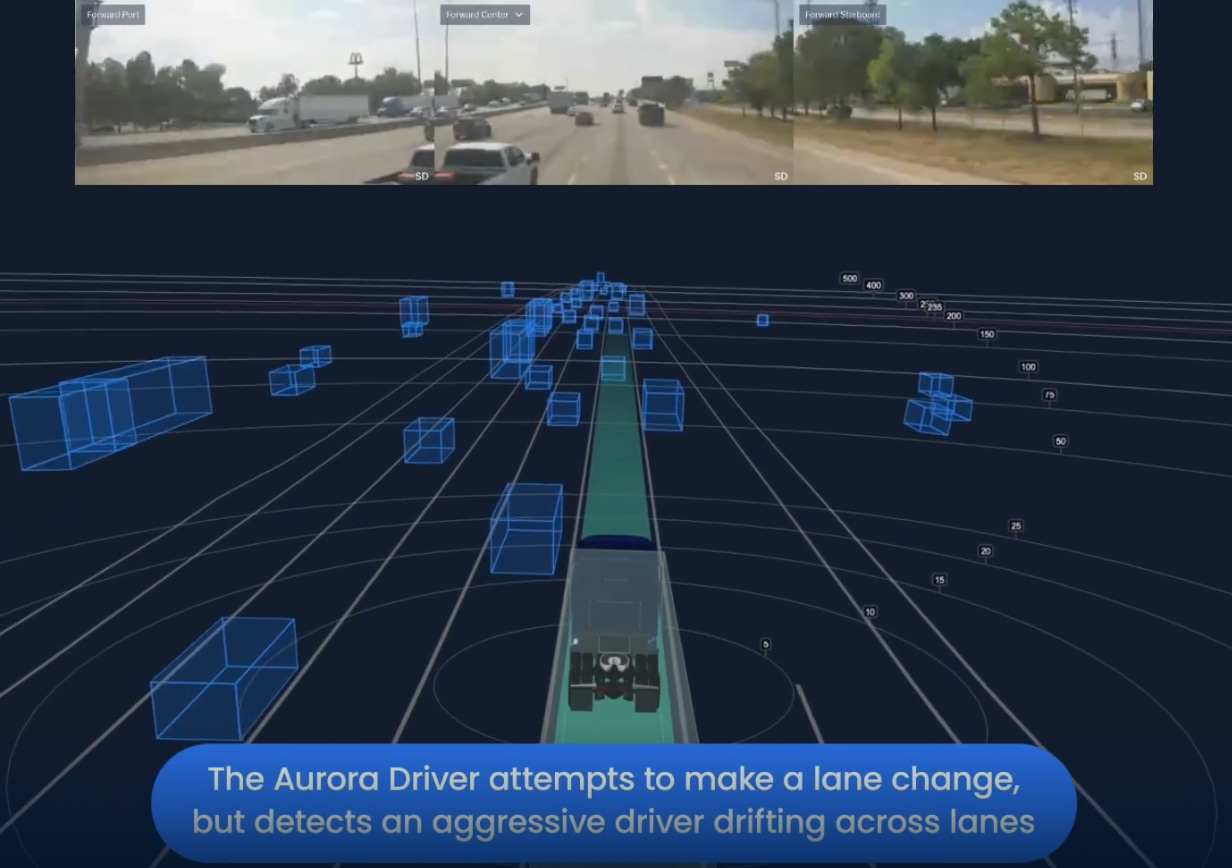

Take, for example, the job of a regional route short-haul trucker, who delivers goods between states without stopping in between. For a robot, in the form of an autonomous semi-truck, to do this job, it must be able to maneuver through a truck depot, hitch in a trailer, drive to the destination, and release the trailer. This is a very routine job, typically filled by one of the 3.5 million truck drivers in the US (circa 2024). Many companies are attacking this, like Aurora Innovation, Kodiak, Torc, Volvo, and others.

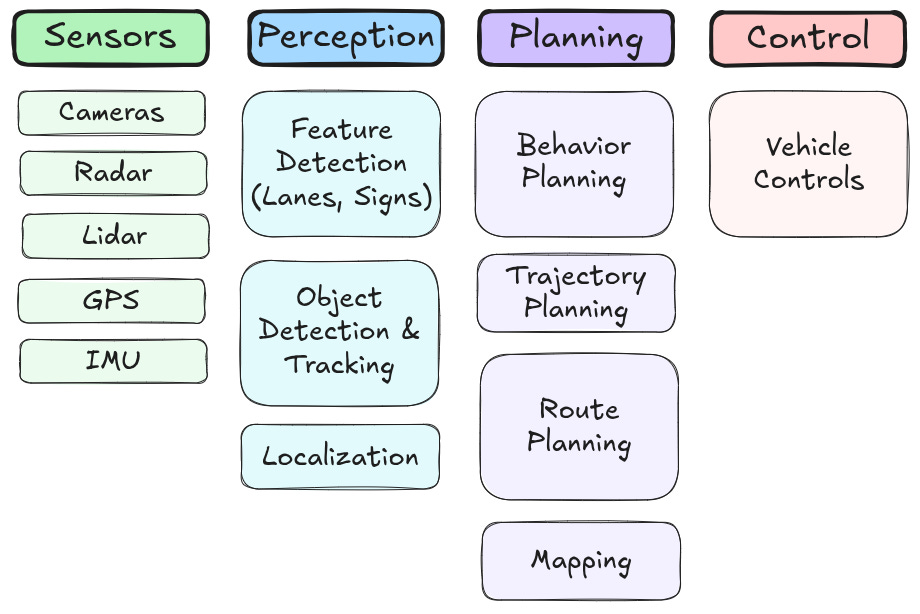

With little to no human assistance, this type of problem can be solved with today’s autonomy stack: sensors that feed into planning nodes to detect objects, open space, lanes, signs, and stop lights. Localizing nodes determine the location of the vehicle in space. And, planning nodes that map out the obstacles and available space, then choose the correct trajectory and the controls required to get there.

While engineers still struggle with the challenges of general intelligence, this type of solution can be effective for routine applications, especially those that utilize street maps. Pair this with selective human control via teleoperation, and it can be applied to many use cases, including taxis, trucking, warehouse logistics, high-volume manufacturing, infrastructure evaluation, mining, landfills, and agriculture. But, this won't be our solution for all the robot use cases people dream about.

Headwind #4: Most robots have not been profitable.

Since their outset, robots fit firmly into deep tech, requiring significant investment and development on both the hardware and software levels. As the industry grew, the cost of developing the robot decreased, allowing more entrants to bring robotics into more markets.

The sad story is that the commercial success stories have been almost exclusively in manufacturing robotics: Kuka, ABB, Teledyne(Universal Robotics), and Fanuc, to name a few. While these robots utilize complex motors, encoders, and controllers, their control system drives the robots along pre-programmed paths, repeating them continuously with little to no adaptation to variations. In some ways, these robots are robots-in-name-only, having more in common with a dishwasher than an autonomous vehicle or humanoid.

The other outlier of success has been Intuitive Robotics, the creators of the Da Vinci system, an extremely impressive surgical tool allowing doctors to control precise movements via manual controls. This tool bears little resemblance to the intelligent robots we have been discussing today.

Instead, many robots are propped up by the belief in a better future. Despite the recent commercial success of Waymo in the US and WeRide in China, neither robo-taxi company has been able to post a profit. This does make sense, on-road EVs need to handle so many edge cases that this was not technically feasible before the recent rise of the LLM and transformer models. On the other hand, many off-road applications can be done with the traditional autonomy stack, yet still, in the construction industry, no company has reached profitability. In that sector, Pronto AI seems to be the only company with a viable path to profitability.

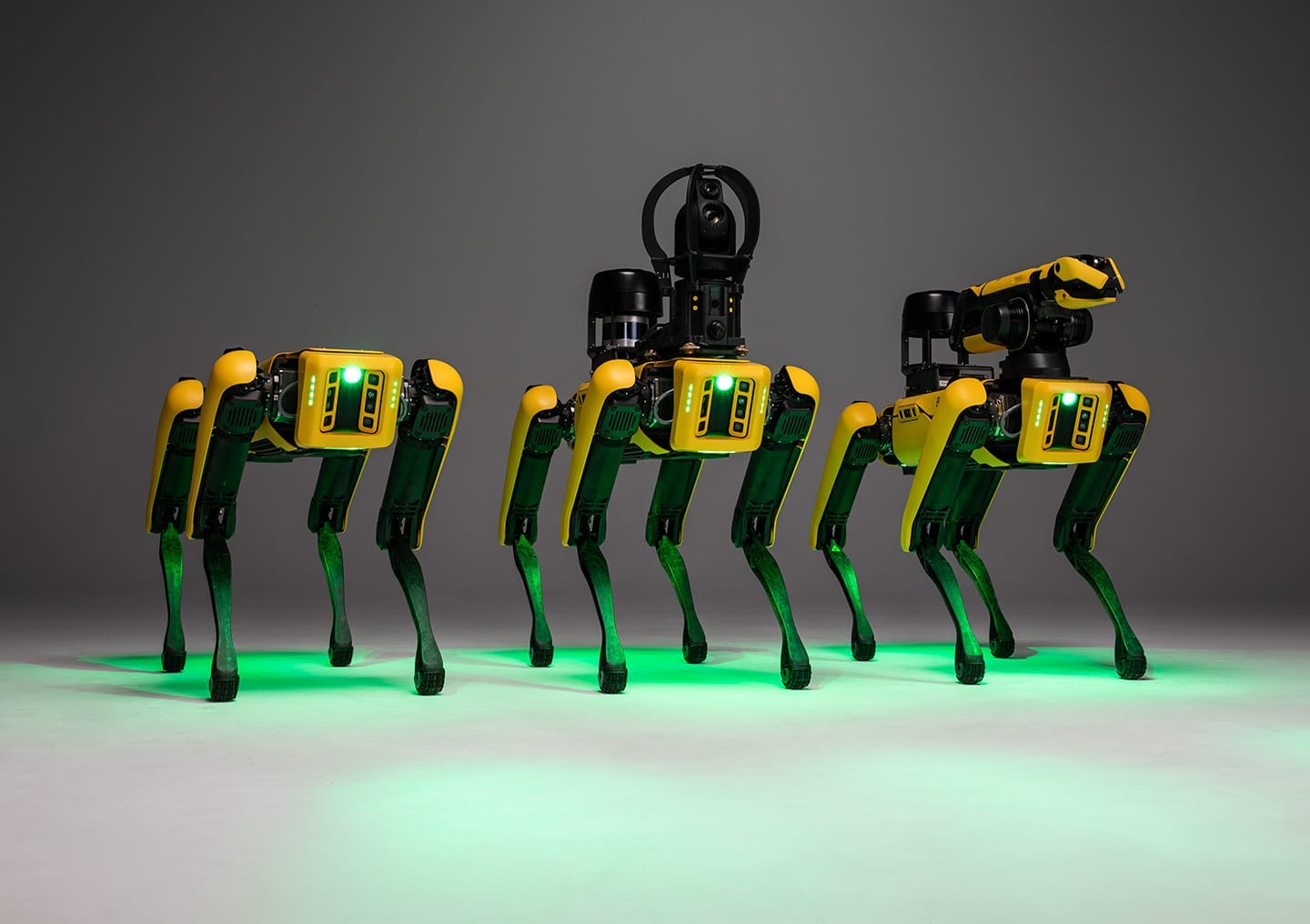

Legged robots haven’t fared much better. Boston Dynamics, famous for Spot the first quadruped, and parkouring humanoids, prioritizes research and has never turned a profit in its thirty years of operation.

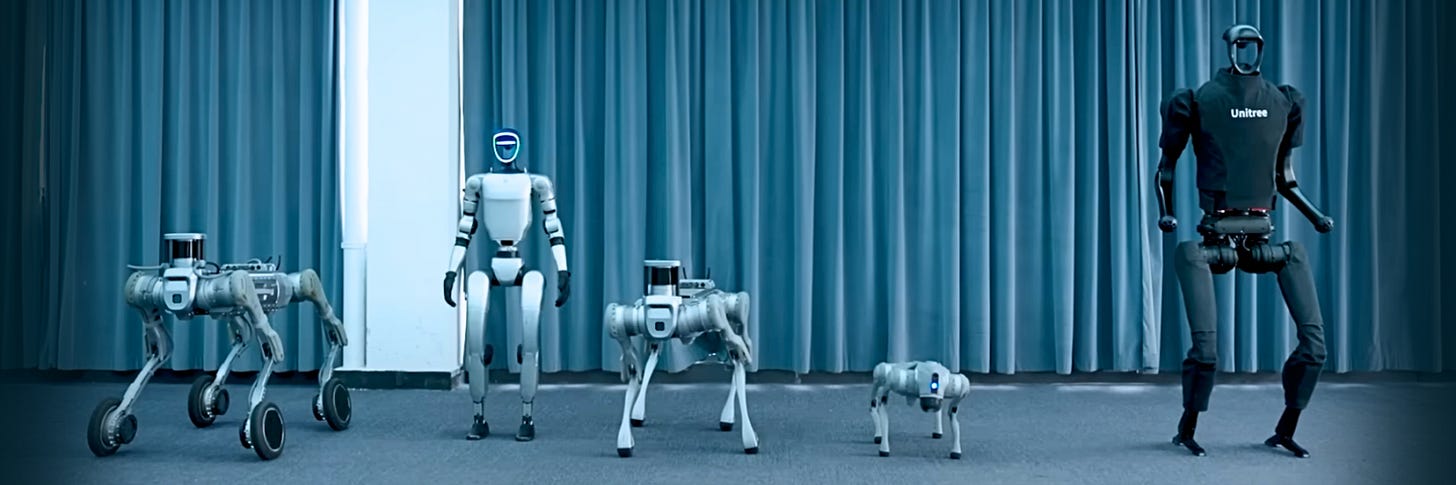

Figure AI and Apptronik, two US humanoid manufacturers, also have no clear path to profitability. They are pouring significant capital into general intelligence, which is necessary for the long-term success of the humanoid and quadruped robotic segments. Generalist robots are only as useful as the general intelligence that drives them. There is one success story: Unitree, a humanoid and quadruped manufacturer out of China, has been turning a profit since 2020. With most of their customers conducting research or education with their robots, they are playing the picks and shovels game. Unitree focuses on hardware, manufacturing, scale, and machine-level controls, leaving general intelligence to those willing to burn cash to pursue it.

This poor track record is a headwind to continued investment and development in the space. New startups in the space need to be ready to answer why they are different than the pile of dead startups that ran out of cash before they balanced the books that were also working on our robotic future.

Headwind #5: Robots are worse at learning than humans

Humans are intuitive learners. We can learn from very few examples and instantly generalize them to many more situations. You can show a toddler a picture of a cat and, from that day forth, that toddler can identify them in different sizes, colors, and environments. Robots, on the other hand, learn statistically, not intuitively, and require photos of many cats of different shapes, sizes, and environments to generalize what a cat looks like.

Humans construct frameworks to understand the world based on common sense and our collected knowledge. New information either integrates into the framework, modifies it, or is rejected. We build it by obsessing over the connections between things, distinguishing between a correlation like moss favoring the north side of the tree3 and a causation like a light switch controlling the illumination of its downstream light-bulb. Robots today primarily operate on correlation and struggle to distinguish it from causation.

Humans learn how to control our bodies in adolescence… hopefully. This means we can learn about actions in an abstract sense, whether it's through written language or IKEA-style picture diagrams. When assembling IKEA furniture, our motor cortex takes care of all the complicated movements, while we focus on lining up dowel pins and finding that last missing screw. Old school autonomous vehicles split up the vehicle control from the trajectory planning, but new robots built off of vision-language-action (VLA) architectures don’t share this feature. Instead, they need to see end-to-end examples of robots very much like themselves doing the action correctly to learn how to accomplish this goal.

So, how do VLA minded robots learn? The core of a VLA is a vision-language model (VLM), which is pre-trained on the video and written content of the wider internet, to recognize objects, words, and actions. The VLA is built around the VLM by adding tools4 and neural nets, the most important of which, the action expert, will learn how to control the robot's physical actions. Next comes domain adaptation training, the pre-training step for the whole VLA model, to teach the robot how to move its limbs and reason in 3-dimensional space. Finally, comes task-specific adaptation, the post-training step that enables the system to learn the specific movements required for the actions it will perform during its service life. The model will then be tested for performance using test data. All of this happens offline to prepare a model for release to a robot.

Despite significant research into online learning, most models are still trained offline to mitigate key challenges such as catastrophic forgetting, intensive compute requirements, and complex data pipelines.

Catastrophic forgetting, for instance, can completely overwrite a model’s existing skills. Let’s say your robot is excellent at folding laundry and putting past-due bills in the shredder, but struggles to put away groceries. You collect a lot of training data of the robot putting away your veggies into the fridge and bread in the cupboard. You want to post-train the model to improve its performance. After the training is complete, you get your wish, and the robot is faster at putting away items into your fridge. The only catch is that the robot forgot what to do with all your bills, suddenly placing your important mail in the crisper drawer alongside your vegetables.

Furthermore, training a model requires significantly more processing power than its inference. It would be inefficient to equip each robot with the oversized, expensive hardware needed only for on-device training, even if all the technical challenges were solved.

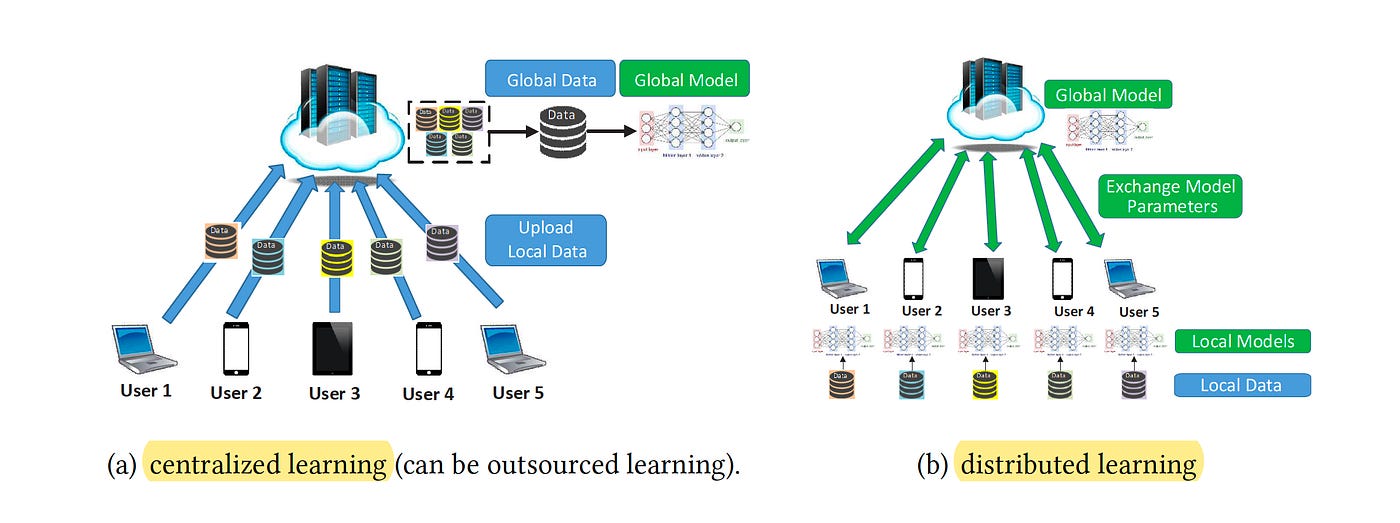

Receiving and selecting the correct training data from past test data is a tricky business. For large, homogenous fleets of robots following the same rules of the road, like Waymo, data can be centralized. What one vehicle learns on the corner of Washington Ave and Lincoln Ave is relevant to all others. Waymo taxis can aggregate the data in a central datacenter, the model can retrain with the new data included in the training set, and the updated model can be pushed out to the robots via over-the-air updates (OTA). However, for the thousand robots operating in unique homes or businesses, this approach fails. Each robot will be subject to different sets of rules. If one robot is scolded for picking up a glass cup, that specific lesson shouldn't become a default behavior for all other robots. This necessitates a central system to act as an arbiter, deciding which rules and feedback are universally applicable and navigating data privacy risks.

It’s getting better

Tailwind #1: The cost of many critical systems in the robot are getting cheaper

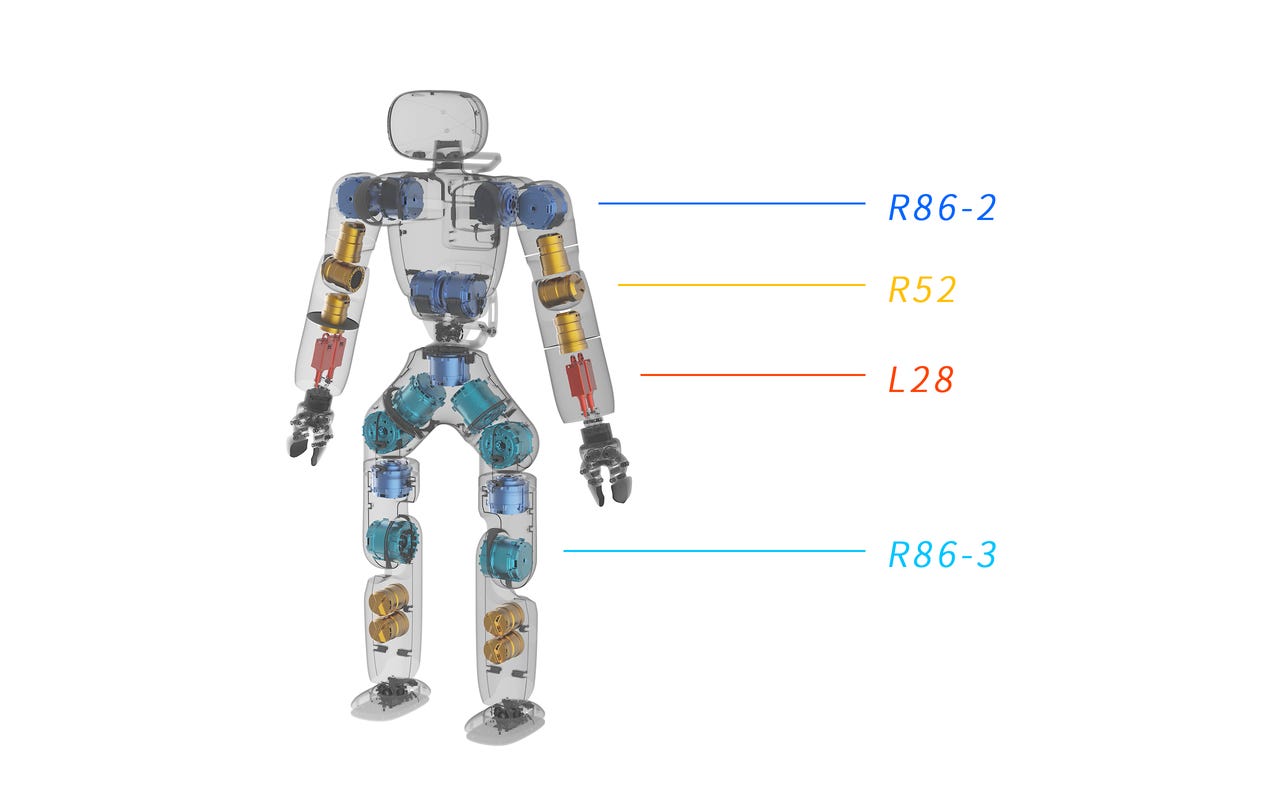

Robots of all shapes and sizes require an extensive list of expensive items, including actuators, power electronics, computing devices, cameras, lidars, IMUs, and batteries. Each item used to be very expensive, requiring all systems that utilized them to be extremely high-value or, in many cases, glorified lab rats.

These systems have had incredible learning curves, the cost reduction rate per doubling of supply. The scale-up of automotive and industrial control systems has increased the consumption of driven actuators and power electronics, resulting in significant cost reductions. Compute has been driven down by Moore’s law and the substantial investments into cloud computing and AI infrastructure. Sensors, such as cameras, lidar, IMUs, and GPS, have been driven down by the scale-up of autonomous vehicles. When I first encountered lidars, a 120-degree FOV unit cost more than $20,000 per automotive-rated sensor; now you can get something comparable for less than $1,000. Batteries, too, have been driven down by the massive adoption of electric vehicles and energy storage systems, coupled with an increase in the quantity and size of high-quality battery production, mostly coming from China.

The cost of robotic components is more than just a barrier for entry, but also a key determinant of which use cases are economically viable. The reduction in component cost has been a major inflection, making things like pool cleaners, in-home vacuum cleaners, and solar installation robots possible. It has helped evolve the market from high-tech research labs to real-world business and hobbyist homes, allowing more people to work towards solving the problems with robotics that we see today.

Tailwind #2: The rise of the transformer model (AI)

Transformer models are supercharging the robotics industry in more ways than one: direct integration, natural language interfacing, increasing development speed, attracting investment, and facilitating data generation/annotation.

The most popular transformer model today(2025) is the LLM. Its performance has sparked the AI craze after the GPT moment in 2022. It uses its deep knowledge of human speech to link words and phrases together to give us a response to our query. When you integrate an LLM and a vision encoder, you get a VLM. This has become the new backbone for the leading robotic models.

Training sets with the text annotated on top of the sound of a word have turned Transformer models like OpenAI’s Whisper or Wave2Vec into key tools for translating what we say into text commands, which can be fed into the robot. Now robots can use these models to receive commands in English or many other languages.

LLMs paired with tools for web search accelerate the learning process for the engineers and researchers working on these complicated problems, making the development of robotics significantly faster. When we added LLMs with iterative reasoning and bash control into coding tools, we leveraged their power to complete development tasks across many parts of the robots, all with a smaller team.

The fervor to invest in AI startups has spilled into robotics, closely correlated with the rebranding of the VLAM model to physical AI. Investors and commercial players are betting big on the role AI plays in our lives, and robots hold a key part of that vision. The capital flow enables more startups to tackle key problems, develop more iterations of models and hardware, and hire more pilots to collect data and train the robots.

LLMs have been used to annotate data, such as driving camera feeds, which are used to identify cars, pedestrians, and runaway baby strollers for autonomous vehicles. They have also been used to generate photo and video data that is used to train future models. This is particularly critical in physical systems, where access to data is a significant bottleneck to creating high-quality models.

Tailwind #3 Moore’s Law

In addition to the reduction of cost mentioned above, Moore’s Law has had a significant impact on another critical dimension of computing, its volumetric density. More compute per unit volume means powerful computers can fit into small packages, like onboard robots and autonomous vehicles, and very powerful compute can fit into reasonable packages, like Blackwells in a datacenter.

Full autonomy, especially for those operating near humans, requires redundancy. Tesla is famous for its parallel processing approach, which utilizes two system-on-chips (SOCs), each containing a set of parallel processors. If one processor fails, that chip’s commands will be ignored, and the other system will continue to operate the vehicle autonomously.

Similarly, for continuous or federated learning to be possible, the power and memory of the robot’s integrated compute must be significant. These are only possible with the miniaturization of silicon, leading to high-performance systems being downsized to SOCs.

One of the most effective approaches to addressing the need for more training data for physical AI can be achieved through high-quality and realistic simulations of robot performance. This includes the rendering of detailed objects and environments, as well as the modeling of realistic physics, which are extremely computationally intensive. Simulation must be done at scale to accommodate the variety of task variations and environmental factors. Lots of powerful compute is the barrier to entry for widespread robotic training simulations.

Where do we go from here? A playbook for success in robotics.

The robotics industry is caught between the incredible promise of our sci-fi future and the practical limitations of today. For aspiring founders, engineers, and investors, navigating this landscape requires a clear strategy. Success isn’t about waiting for all the headwinds to dissipate; it’s about choosing which battles to fight right now.

Path 1: The pragmatic path

This strategy focuses on creating a commercially viable company within the next 1-3 years by leveraging lessons learned from the last wave of robotics companies. Instead of trying to create one robot that does everything, the goal is to build a solution that excels at one high-value task.

Your call to action: Don’t try to boil the ocean. Hunt for opportunities that are dull, dirty, or dangerous. Solve problems that are repetitive, undesirable, expensive, or unsafe for humans. A successful use case will meet these criteria:

It’s a specific problem: It targets a single, repetitive set of functions in a controlled environment (warehouse, lab, mine). This does not require general intelligence and is solvable with today’s technology.

It has a clear ROI: The task must be expensive enough that automation offers a clear, rapid payback. The robot should add clear value beyond just wage replacement; its job well done should be noticed on its customer’s P&L. This counters the “robots aren’t profitable” headwind and is the most critical factor for driving customer adoption.

Path 2: The moonshot path

The high-risk, high-reward path is for those who want to build future robot protagonists. Companies here, like those building humanoids and general-purpose platforms, are leveraging transformers and more powerful compute to tackle the data and learning headwinds head-on. This is a 5-10 year play backed by significant capital.

Your call to action: Seek out the best-funded research labs and corporate R&D divisions. The goal isn’t immediate profit, but contributing to the foundational AI models and platforms that will define the next decade. Success looks like being part of a team that either becomes a market-defining giant or a key acquisition for a major tech player.

Setting Realistic Timelines

Path 1 specialists (1-3 years): Adopted in targeted industries. The invisible workhorses of factories, farms, and warehouses.

Path 2 generalists (5-10+ years): Adopted both commercially and residentially. They will become a key part of our daily lives.

The opportunity in robotics is immense, but it demands strategy to avoid the scrap heap of failed ventures from our recent past. The question isn’t if robots will transform our world, but how. The most successful ventures will be those that choose their battles wisely, solving today's problems while keeping an eye on the promise of tomorrow.

I do not include most manufacturing applications of industrial robots, because most six degrees-of-freedom (6-DoF) and 7-DoF arms that follow pre-programmed paths are machines in my book.

Pronto AI is an autonomous company specializing in dump truck hauling within the mining industry. They are the only construction autonomy company with a viable path to profitability from the first wave of construction tech.

The fundamental rule of moss growth is that it thrives in cool, damp, and shady environments. In the Northern Hemisphere, specifically north of the Tropic of Cancer, the sun's path is predominantly in the southern sky. This means the north side of a tree typically receives the least direct sunlight, creating the perfect microclimate for moss to grow. However, this is a reliable tendency, not a law. Local terrain like hills, mountains, or even a dense forest canopy can cast shadows anywhere, allowing moss to grow on any side of the tree. Following the same principle, moss in the Southern Hemisphere is more likely to be found on the shadier south side.

VLMs are pre-trained on vast 2D datasets, like internet videos, which are typically shot from a third-person perspective. While excellent for scene observation, this data poorly prepares a model for acting from a robot's first-person, 3D viewpoint, resulting in weak spatial reasoning. To bridge this gap, researchers have found that decomposing a robot's complex 3D sensor data into a set of 2D views, a format more akin to what the VLM has already seen, significantly enhances its reasoning capabilities. A function that performs this 3D-to-2D translation is a perfect example of a specialized 'tool' that can be integrated into a more capable VLA model.

This is genuinely one of the most thoughtful and comprehensive robotics analyses I've read all year - excellent work Xavier! Your framework of custom-purpose vs. general-purpose robots, and the challenges around data, embodiment, and profitability, perfectly captures why we're still waiting for the sci-fi future. On Kodiak specifically: they're emblematic of your 'pragmatic path' strategy. By focusing on long-haul trucking (repetitive, structured, dangerous, expensive), they've chosen a battle that's winnable with today's autonomy stack. The fact that they've already delivered factory-built trucks to Atlas Energy (8 of 100 so far) shows real comercial progress, not just lab demos. What I find particularly interesting is how the defense contract ($50M) provides revenue diversification while they scale civilian operations - a hedge against the profitability headwind you identified. Your point about VLA models needing end-to-end examples resonates here: Kodiak is accumulating exactly that data on real highways, which compounds as a moat. The irony is that while humanoids get all the hype and VC dollars, freight autonomy might be the first true moonshot to actually land.